In writing my recent book, Split at the Root: A Memoir of Love and Lost Identity (Kindle) or Split at the Root: A Memoir of Love and Lost Identity, I tell the story of growing up within a culture and a race that was different to my own. Here’s an excerpt:

In writing my recent book, Split at the Root: A Memoir of Love and Lost Identity (Kindle) or Split at the Root: A Memoir of Love and Lost Identity, I tell the story of growing up within a culture and a race that was different to my own. Here’s an excerpt:

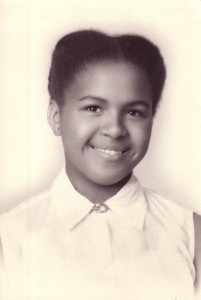

I was passing by Vati’s room one afternoon; we still called it Vati’s room although he had died over a year ago. Two upholstered chairs and a small round table with a reading lamp took the corner space where his bed had been. Mutti was sitting at the massive mahogany desk that remained as it had, facing the garden. “What do you think of this poem Mohrle?” I heard her call to me. I entered the room and took the paper from her hand. The date on the top left corner read October 1952. She was sixty-four then, I twelve.

“It’s beautiful Mutti, honestly,” I said after reading the words, and felt she must have been a little sad, for her writing conveyed a deep nostalgia for the hills, valleys, and chatty brooks of the Pfalz, the countryside of her youth. “I didn’t know you wrote poems,” I said pulling a chair over to sit next to her desk. “Please tell me again about the Pfalz. Tell me again about Germany,” I begged. And so began another of those afternoons when my mother offered me glimpses of her youth.

“The Pfalz, long ago Mohrle,” she smiled mildly, “was part of the Holy Roman Empire.”

“Roman? Like Julius Caesar, Roman?”

“Yes,” and I could tell her sadness was gone. “The Romans made themselves comfortable on the banks of the Rhine and began to cultivate grapes. Those people loved their wine,” she raised her hand like taking an imaginary sip. I had seen pictures in the National Geographic of terraced land along the Rhine.

In melodic mellow tones, Mutti brought back the beauty of the fields and streams where she had wandered in her youth; and I learned about geography and history, about the Romanesque, Gothic, and Baroque cathedrals and castles that dotted the landscape. As Mutti talked about princes, electors, and archdukes, my mind filled the spaces with pictures of armor-clad knights singing to golden-haired princesses in towers, like in the drawings of Andersen’s fairy tales. “When you finish high school I’ll take you to my beloved Pfalz, and we’ll stroll over the cobblestoned streets and you can run in the fields and skip on pebbles in the chatty brooks as I did,” she promised. And so, the Pfalz became more and more a part of me. So much so that I never questioned it could not be, not even in the farthest recesses of my mind.

Most people spoke French and German because the Pfalz was a buffer state between France and the German principalities. “The simpler people made up pretentious words. For instance,” Mutti laughed at the recollection, “regular soap is ‘Seife,’ as you know, but when the soap came from France, the simpletons called it ‘savon-seif’ – soap-soap,” and she contorted her face to make it look really boorish. We burst out laughing, and together chanted “Saffon-seif, saffon-seif!” and I squinched my face like she did, and we continued to laugh and laugh.

What I loved most were her colorful descriptions of the food; the clear white wine she said was “the nectar of gods and a gift to the educated palate.” Liverwursts and bratwursts seasoned with aromatic herbs were served on a bed of Sauerkraut that had been cured in champagne and sweetened with apples and grapes; and the crusty, grainy dark bread with a slab of fresh butter must have been divine, because Mutti had not given up trying to get the maids to replicate it.

I wanted so much to be a little like Mutti, or at least a little like the people in the Pfalz. I knew the answer, so did not ask why my nose was small when she said the Pfaelzer, like the French and the Italians, have large noses. Mutti’s eyes were not Nordic blue like Vati’s but hazel, and before years left silver strands, her hair was chestnut with auburn highlights. Ruth was also a brunette, had a large nose, and chocolate-colored eyes. They all looked alike: Tante Gustl, who was four years older than Mutti, and Tante Lisl, who was two years her senior. The former lived in Güntherstal, deep in the Black Forest, the latter in Saarbrücken on the border with France. Sight unseen, I loved everyone in that family and I dreamed of meeting my aunts and uncles, my many cousins and everybody else I was hearing about.

Like an oasis in the desert that attracts all water within its reach, I thirsted for Mutti’s stories. With each one, I became more and more her child; her family was my family, her history my history. I had ancestry that dated all the way back to Julius Caesar; I had a family in Germany; I had aunts, uncles, cousins. In my subconscious I knew better, but I adopted them all as my own and they became an integral part of the framework that offered me security. The contentment of belonging to such a fine group of people and having such a wonderful history left no room to squeeze a serious thought about my own background. I didn’t think to ask about Rosa and her community; I wanted only to know about Mutti’s world.

Read more: Split at the Root: A Memoir of Love and Lost Identity (Kindle) or Split at the Root: A Memoir of Love and Lost Identity.

SEP